Curious about tonic water’s health benefits? You might be surprised. While it adds a zing to your gin, tonic water may not be as healthy as you think. Discover the truth about its sugar content and healthier alternatives.

If you love the taste of tonic water, recent research shows you might just have a bigger brain than the rest of us.

The short answer: No.

In fact, “tonic water” is a bit of a misnomer. Sure, the bubbly drink starts out as carbonated water, and then quinine — a bitter alkaloid once used to treat malaria — is added.

Nothing wrong with that, but most store-bought varieties also add fruit extracts and sugar. When you add 4 ounces of tonic water to a standard cocktail, you’re sipping on 11 grams of sugar — just as much as if you’d poured 4 ounces of Sprite.

We already know that too much sugar is bad news. A 2019 study showed that the more sugar-sweetened drinks we consume, the greater our risk of early death from cardiovascular disease and cancer, particularly among women.

Sometimes, the sweetness in tonic water comes from high-fructose corn syrup, but the news there isn’t much better. In 2015, researchers found a link between drinking syrup-filled beverages and a greater risk of heart disease.

Tonic water seems like it would be in a different class than the soft drinks we think of when we hear those kinds of statistics. But if you take a gander at the nutrition labels on a bottle of tonic water and a bottle of Coke, you’ll notice the two have an almost identical number of calories.

Obviously, most of us consume Coke and tonic water differently — maybe drinking a whole can of the former but using just a few ounces of the latter to complement a cocktail. So, while that first gin and tonic isn’t something to worry about, the added sugar becomes a concern when you’re on your third or fourth.

Unfortunately, making healthier choices isn’t as simple as opting for diet tonic water. Calorie-free sweeteners like aspartame (Equal) and saccharin (Sweet’N Low) are a bit scandalous in the health world.

Some researchers believe that artificial sweeteners prep your body for a sugar fix and then don’t deliver. According to a 2010 study, if you’re left craving sweets after you slurp down a soda, you’re more likely to eat — and keep eating.

In 2013, researchers decided to test this theory. They had 200 people replace their sugary drinks with diet varieties or water for 6 months. The conclusion? Diet-beverage drinkers actually ate fewer desserts than the water drinkers, so there’s that.

A 2017 review noted that the long-term impact of sweeteners is not yet known. And they do little in the way of weight loss. In fact, the opposite may be true: Sometimes diet-beverage drinkers gain weight and have an increased risk of chronic diseases.

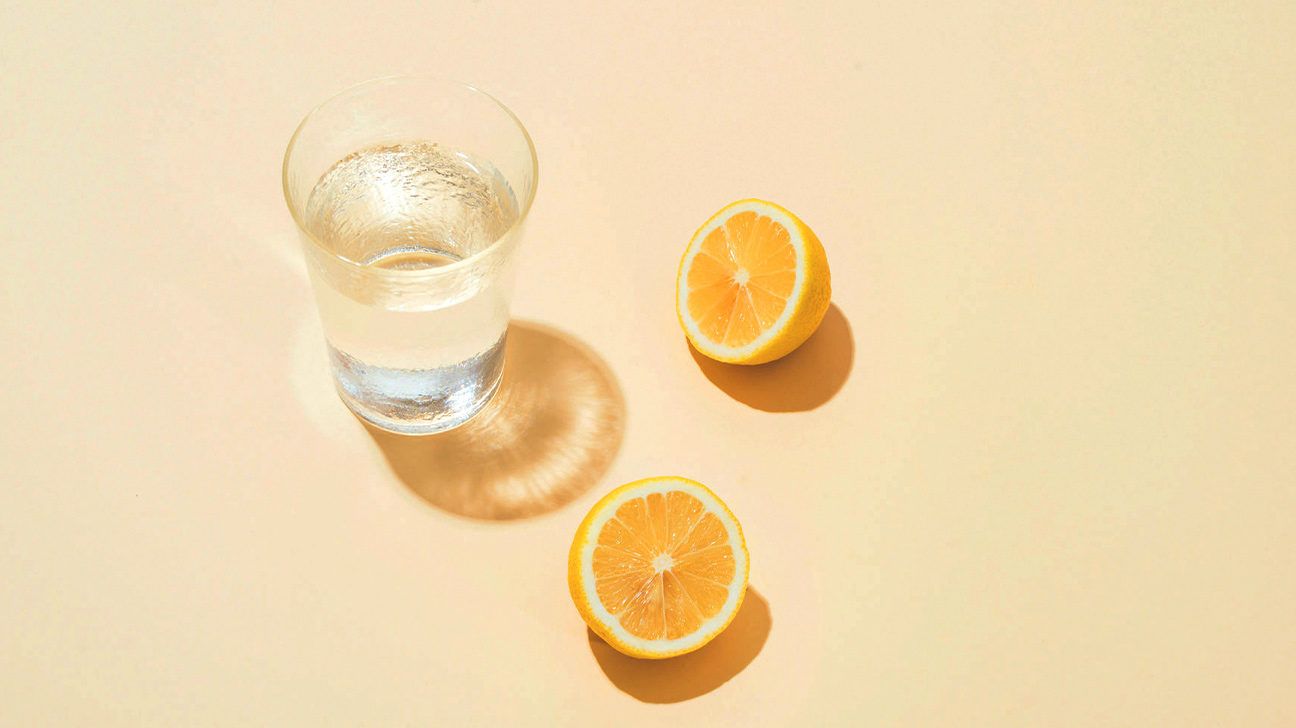

We’re all for a classy gin and tonic now and again. But instead of tonic water, maybe reach for seltzer, which is usually straight water with bubbles.

Add a squeeze of lemon to enhance the flavor. And if you’re using the seltzer as a cocktail mixer, toss in a few bitters to mimic the taste of quinine. Cheers!