If you’re new to the beer scene, I have some bad news: There are a lot of different kinds of beer. Telling a bartender you’d like a beer, please isn’t going to get you very far. They will have questions.

If you’ve ever had a slight panic attack in a liquor store trying to figure out what to bring to a cookout or party when your friends say, “Hey, can you grab some beer?” then you know what I mean.

Here, then, is a primer for all your basic beer selection needs so you can fearlessly conquer the next tap list or tailgate party that comes your way.

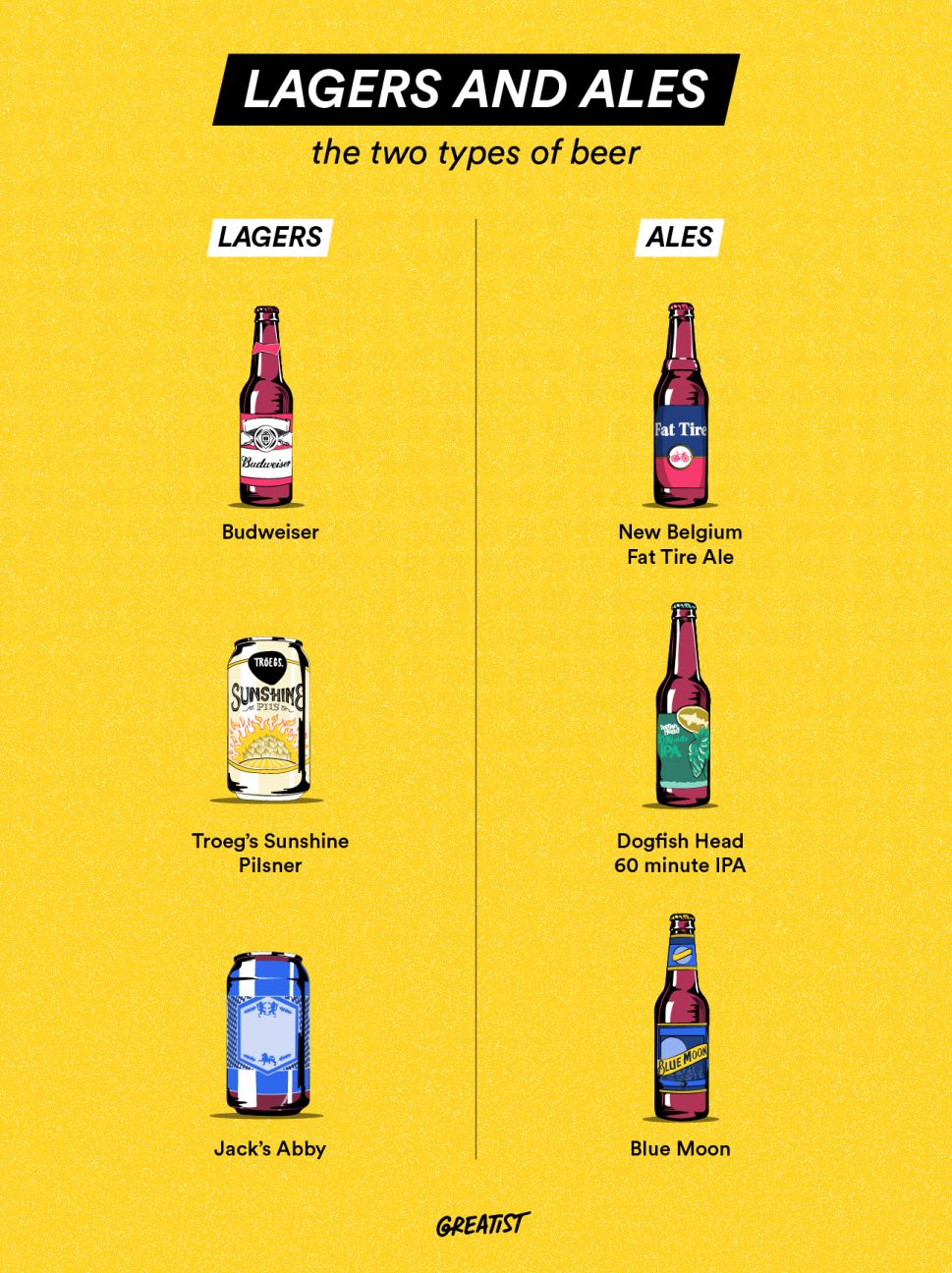

While there are dozens of styles of beer, there are truly only two types of beer: lager and ale. Everything else splits off from there — kind of like how the grouping system used to classify living things starts with kingdom, the broadest specification, and narrows down all the way to species, like so:

Ale → Pale Ale → India Pale Ale → Sierra Nevada Celebration IPA

or

Lager → Pilsner → Idle Hands Edgeworth Pilsner

The main differences between lagers and ales are the type of yeast and the brewing temperature. Ales are made with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, the yeast used in baking bread, and fermented between 60 and 75 degrees Fahrenheit. Lagers are fermented between 45 and 55 degrees and made with Saccharomyces pastorianus.

When it comes to drinking them, ales are typically full-bodied and sweeter-smelling, like New Belgium’s Fat Tire Amber Ale, while lagers, like the beers of Budweiser and Miller, are crisp and clean, the kind of drinks you reach for when it’s hot out.

“IPA” stands for “India pale ale.” These beers are characterized by a bitter (in a good way) wallop of hops and a higher-than-average alcohol by volume (ABV), usually around 7 percent.

When the British were out colonizing India in the 1800s, soldiers were desperate for something cold and boozy to come home to after long days of imperialism in the tropical heat. But it’s a long boat ride from England to India, and most of the beer onboard the ships arrived spoiled.

Desperate to make a beer that would last the journey, brewers beefed up the alcohol content (for preservation) and added hops to the barrels before sealing them (for a fresher taste).

Brewers of American IPAs today follow a similar method called dry-hopping, adding hops to already-fermented beer for extra flavor instead of introducing them into the mash.

There’s a ton of variety among IPAs, but most fall into one of two camps, a West Coast IPA or a New England IPA. While each style originated on its respective coast, breweries across the country can and do produce either one and often brew both.

West Coast IPAs

West Coast styles, like Sierra Nevada and Firestone Walker’s Union Jack, are bright, highly carbonated, and very, very hoppy.

New England IPAs

New England IPAs, like Lord Hobo’s 617 and Maine Beer Company’s cult classic Lunch, are less bitter, often more fruit-forward, and unfiltered. They often look like orange juice coming out the tap.

Wheat beers are a type of ale, and they’re exactly what they sound like: beers brewed mostly or entirely from wheat. Wheat beers are generally hazy, light, and citrusy and have a fuller mouthfeel, like Allagash White and Weihnstephaner’s hefeweizen. These beers use few hops and are generally easy drinking.

“Saison” translates to “farmhouse ale.” This type of beer was originally brewed in the fall and stored for refreshment for Belgian farm workers in the warm summer months. Saisons can be considered the original craft beer, since each farmer typically had their own recipe and incorporated hops and yeast from their land.

Because saisons are unique by legacy and design, there’s a lot of variety in today’s taps and bottles. But all stay true to the original philosophy: Be light, be refreshing. Two Roads’ Worker’s Comp Farmhouse Ale is a contemporary classic.

Pilsners (or just pils) are pale lagers noted for their ultra-crispness. Originally brewed in what is now known as Pilsen, Czech Republic, in the mid 1800s, the Czech Pilsner was the answer to the traditionally dark and heavy beers of the area.

Made with the light-colored local (Pilsner) malt, a bottom-fermenting local yeast, Pilsner beers are extremely well-balanced — some even say artistically so.

Foundation Brewing’s Josef Pils pays homage to the original Czech brew and brewer. Victory’s Prima Pils is a bright contemporary spin on the classic.

Porters and stouts are both (very) dark ales brewed from barley. Genealogically, porters are the grandparents of stouts: Stouts came along when brewers started to tinker with recipes for porter.

The biggest difference is that stouts are brewed with unmalted, roasted barley and porters are made with malted barley.

Porters

Porters, like Foolproof’s Raincloud Porter and Maui Brewing’s Coconut Hiwa Porter, are lighter, with malty sweetness and a slight amount of hop.

Stouts

Stouts are more robust and fuller-bodied, often with underlying coffee notes. Guinness’s Irish Stout is recognized worldwide, but there are plenty of options for this dark, dark beer style.

Sour beers are, well, sour. Their characteristic tartness comes from wild yeast strains or bacteria that brewers intentionally allow into the brew while it ferments.

While sour beers today can have fruits added for extra flavor notes, like Funkwerks’ Raspberry Provincial, sour beers are not fruit-based like ciders or sparkling wine. The old-school sour beer style, the German gose, has no fruit component (and actually incorporates salt).

Session beers are any style of beer with less than 5 percent ABV — so they’re a good option for all-day drinking events or extended drinking sessions.

All “light” beers are session beers. Bud Light (a lager) is probably the most widely consumed session beer, although it’s not marketed as such. If you’re looking for variety, flavor, and a low alcohol content, Notch Brewery produces a variety of styles of beer all with less than 5 percent ABV.

“Craft beer” is the term used to differentiate the products of smaller, often (but not always) independently owned breweries from those of the corporate giants like Budweiser, Miller, Heineken, and Corona.

Much like “local” and “organic,” “craft” denotes a small(er) scale production, close(r) ties with the local community, and often intentionally featured ingredients from the region of the brewery. “Craft” doesn’t imply a specific style of beer, although many craft breweries are known for certain styles.

Jack’s Abby, for instance, makes only lagers but produces several beers, while Night Shift Brewing makes (or has at one point made — they’ve had several limited releases over the years) at least one of nearly everything on this list.

Haley Hamilton is a Boston-based bartender and freelance writer. She writes about booze, bars, drinking culture, and millennial angst. Her writing appears in Eater, Bustle, PUNCH, and MELMagazine. You can find her infrequent retweets and musings on Twitter.