As a medical journalist and fact checker, I’ve been all about the numbers during the COVID-19 pandemic. One number I’ve been hyperfocused on is how many people in the United States say they’re willing to get a COVID-19 vaccine.

A Pew Research Center poll in December 2020 found that only 60 percent of Americans would definitely or probably get a shot. That number had gone up from 51 percent in September. But it’s still not ideal, according to experts like Dr. Anthony Fauci, the nation’s leading infectious disease expert.

I have severe eosinophilic asthma and an autoimmune disorder. So there’s no question I’ll get the vaccine when one is available to me in the coming weeks. It’s the only way I’ll feel safe in public again, be able to teach my university course in person again, and — most importantly — be able to get on a plane and visit my immunocompromised parents, whom I haven’t seen in more than a year. Although I know getting the vaccine won’t get me back to pre-COVID life, it will be a big step in a better direction.

But I want to put myself in the shoes of anyone who is vaccine-hesitant. For some people, a completely new vaccine for a novel virus is a frightening thing. So here I’ve explored some common questions and concerns, done the research, asked the experts, and found some answers. Let’s unpack it.

“The greatest gains in infectious diseases in this century, and the last, has been in the development of vaccine,” says Dr. Nasia Safdar, the medical director of infection control at University of Wisconsin Hospital and Clinics and a professor in the department of medicine at UW’s School of Medicine and Public Health.

Before 1963, nearly all children got the measles by the time they were 15. Many of those who were infected developed encephalitis and long-term complications, and the virus was responsible for tens of thousands of hospitalizations and hundreds of deaths each year. A vaccine became available in 1963. But, as Safdar points out, we don’t have a treatment for measles.

“The fact that we have this highly effective vaccine has meant the difference between kids living with measles and dying of measles — as is still happening in many countries where people don’t have access to the vaccine,” she says. “To see the ravages that these preventable diseases cause, you have to go back several decades in this country, or you have to visit a country where the vaccine is not available. And if that doesn’t convince you, then nothing will.”

In a perfect world, we wouldn’t have a pandemic on our hands. But since we do, we have to think about a perfect world where a novel virus has killed well over 2.4 million people globally.

“There are two ways of curbing a pandemic,” says Safdar. “You can either have natural disease in most of the population — such that people recover and become immune — or you can have a vaccine which artificially induces that immunity.”

By this point, you’ve possibly heard about the “herd.” That’s us. We’re all this great big herd. Immunity means that you, a person in the herd, cannot transmit. So if you’re immune to a virus and someone who has the virus sneezes on you, you can’t unwittingly give that virus to Grandma at her birthday party.

Now, herd immunity is the dreamy-dream goal. But again, to achieve that herd immunity for a virus and offer protection to the remainder of folks out there, generally about 70 to 90 percent of a population needs to be immune to infection.

As Dr. Safdar outlined, there are two ways to get there: infection or vaccination. And having an infection is no guarantee of immunity or the reduced potential for transmission.

“The first option is not very appealing,” she says, “because, of course, no one wants people to have to get sick from an illness where the outcomes are very uncertain. And we’re still learning that several months after COVID-19, people are still having trouble getting back to their usual self.”

Well, here’s a tl;dr answer to that question: “It isn’t a responsible strategy anywhere,” says Dr. Ashwin Vasan, assistant professor of clinical population and family health and medicine at Columbia’s Mailman School of Public Health and president and CEO of the mental health nonprofit Fountain House.

“But it’s particularly irresponsible in a society like ours with vast structural inequalities and disparities in health and social welfare,” he adds, “which will result in the burden of that herd immunity strategy falling on people who are already at the margins of society. That’s not a moral or an ethical, let alone effective, response.”

Now for the longer answer: To achieve herd immunity through infection alone, most of us have to contract the virus. So how’s that going for us? Well, to achieve even the bare minimum 70 percent infection rate required for herd immunity without a vaccine, more than 200 million out of 330 million people in the United States would have to contract the virus.

Based on a recent Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimate of COVID-19 infections from February through December 2020, about 83.1 million people may have been infected in the United States. We’re less than halfway there, and we’ve lost half a million people who are parents, grandparents, spouses, children, friends, etc.

I’m really glad we have vaccines now to hopefully reduce the loss of life. Aren’t you?

The first thing to realize is that a vaccine can’t do anything if people don’t go out and get it. If a fire breaks out and you’ve got access to a fire extinguisher, isn’t it a no-brainer to take aim? And if it’s a big fire, the more people you have trying to put it out, the better.

Right now, there are two COVID-19 vaccines available in the United States: the Pfizer-BioNTech and the Moderna vaccine. Both have received emergency use authorization (EAU) from the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), and they require two shots several weeks apart. But more vaccines are in the pipeline, undergoing phase 3 clinical trials and the application process for EUA.

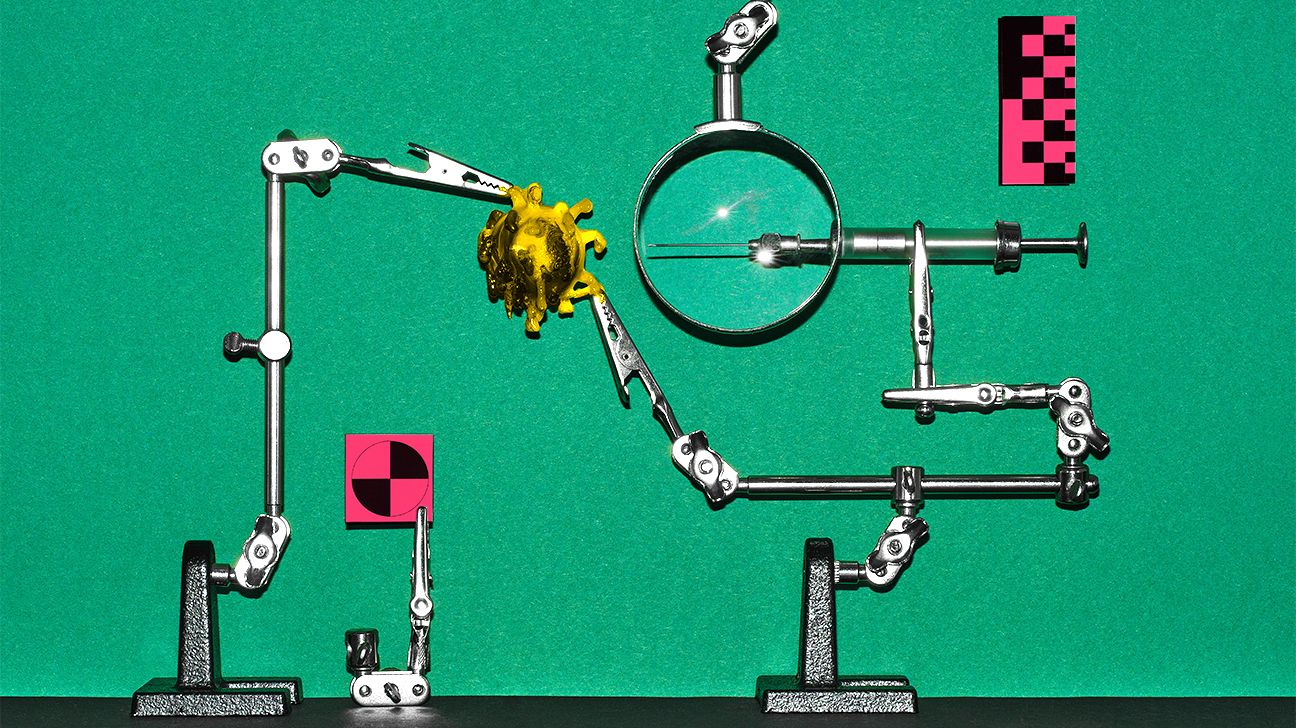

Both of these messenger RNA (mRNA) vaccines teach our cells to create a part of the spike protein that’s found on SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19. Our immune system then sees this spike fella and decides it doesn’t belong. So it builds an immune response by making antibodies and T cells.

Then, if you come into contact with the actual virus later on, your body remembers its immune response and gets to work fighting off that bad guy ASAP. No actual virus goes into your body with an mRNA vaccine. And no, your DNA is not changed through vaccination. That’s a myth.

The available vaccines have an effectiveness rate of about 95 percent once you’re 2 weeks out from receiving that second shot. That means there’s a 95 percent chance whichever vaccine you get will protect you from getting sick with COVID-19. However, experts are still studying whether vaccinated peeps can contract an asymptomatic infection and transmit it to another person.

And that’s one of the reasons life doesn’t morph back into some sort of pre-corona unicorn once you’re vaccinated. You still need to do all the same jazz: Wear your mask, maintain a 6-foot distance from others, avoid crowds, practice good hand hygiene, etc.

And we’ll be doing those things for a while, especially if only 60 percent of Americans get the vaccine. “If that number doesn’t move, then we’re not going to get to where we need to go,” Vasan explains.

But if most people grab for that fire extinguisher…

Some people worry about vaccine risk. The CDC has released a report now that more than 22 million people have received a COVID-19 vaccine in the United States. The report shows the vaccines are safe and associated with few serious side effects, though we still have more to learn about any long-term effects.

But in general, serious side effects from vaccines, although not zero, are extremely rare. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services website says, “For example, if 1 million doses of a vaccine are given, 1 to 2 people may have a severe allergic reaction.”

Some cases of severe allergic reactions (anaphylaxis) to COVID-19 vaccines have occurred. As an EpiPen carrier myself, I get it. The A-word is scary. But the CDC reports that these instances of allergic reaction are rare and comparable to those reported for other vaccines. Vaccine administration sites, doctor’s offices, and pharmacies have safeguards in place in case an allergic reaction occurs.

“Calling it ‘Operation Warp Speed’ [was] probably not good messaging, because people think you’re making sacrifices in safety in order to get something to the market quickly,” Vasan says of the Trump administration’s name and vision for an available vaccine ready to go ASAP.

At one point, the world had more than 100 projects dedicated to finding a COVID-19 vaccine. Although we have only two jabs available in the U.S., others have been approved elsewhere. And at least 20 of them are in the final stages of testing. Some have been abandoned altogether. So yes, there has been, and still is, a race for a vaccine — but let’s dive into what that really entails.

“Vaccines have to go through this very well-laid-out, very vigorous plan for assessing two things,” Safdar says. “One is safety and the other is efficacy, and both of those things have to be very strong for the vaccine to be out in the population.”

A Phase III trial to test if a vaccine is effective involves thousands of people. And before a vaccine even reaches that stage, it’s been tested on volunteers in a Phase I safety trial and a Phase II expanded trial.

In the United States, the FDA is responsible for regulating vaccines and requires drug developers to adhere to a strict process. You may have heard that the FDA has given “fast-track” designation to some vaccines in the works.

“The accelerated time frame for a vaccine doesn’t mean that any of these steps have been short-circuited or skipped altogether,” Safdar explains. “Rather than having it in [the FDA’s] usual flow of putting things in a queue and reviewing them when they come to that spot in the queue, they’re fast-tracking them, meaning that they’re pushing them to the top of the queue.”

COVID-19 was the leading cause of death in the United States for 2020, so as a health crisis it has received top priority. And a vaccine has been one of the biggest priorities for pounding down the pandemic.

Vaccine risk, rare but not zero, isn’t the only risk in the equation. Here’s the full set of risks to consider: “On the one hand,” Vasan says, “you’ve got the potential risks of a vaccine,” a risk he says is relatively minimized once the vaccines has received EUA. “On the other hand, you have this very real and documented risk of getting coronavirus.”

He adds that you could die from the virus, endure long-term complications, or transmit it to someone more vulnerable than yourself — if you don’t fall into the high risk category yourself.

The CDC lists broad categories of people with heightened risk for severe complications. But the reality is more complicated.

“Even young people are suffering pretty dire consequences,” Safdar explains. “Without the ability to predict severe illness, death, and long-term complications, there’s only one solution. Most people in a population need to be vaccinated to protect themselves and each other.”

Another consideration is that vaccine hesitancy is a very real threat to the world. “WHO has identified that as one of the greatest public health threats of the next era — the next 10 years and beyond,” Vasan says. But if you do the research, get beyond the fear, and get the vaccine, others you know may follow. If you spread fear, however, the opposite can happen.

During a pandemic, disinformation can spread much like a virus. And we’re all responsible for stopping that spread. A big key here is that we can’t assume memes or Cousin Tommy’s social media posts are truth. Consider whether you can click on a link in a post and be taken to a reputable, unbiased source.

When I teach media literacy to university students, I encourage them to use this chart in choosing a news source. It categorizes news organizations on their reliability and impartial reporting.

Additionally, if you want to investigate a post or claim, plug it into a fact-checking site. For example, there’s a viral image going around that states “Four kids who took the coronavirus vaccine died immediately.” You can simply search “vaccine” on PolitiFact, which is run by the Poynter Institute, and quickly learn that the claim is false.

“Find one or two trusted sites where science is leading the way,” Safdar suggests, “whether that’s your local department of public health, whether that’s the CDC website or the NIH website, those are the places to go to for vaccine information.”

When you’re in doubt or worried about disinformation from the higher reaches of government, always focus on the science. “Trust the scientists who are reviewing these studies, talking about these studies, and publicizing these studies,” Vasan says. “We’re guided by the right data. We’re not guided by power and political gains and by votes.”

ASAP! Depending on your circumstances, you may not have access to the vaccine yet. Check your state’s health department website for availability. “If it becomes available to you,” Safdar says, “that’s an opportunity you should avail yourself of.” Make a plan to rally friends or family members (who have it available to them as well) to go with you — while practicing social distancing, of course.

And although we don’t know the specifics on a COVID-19 vaccine yet, keep in mind that you won’t have an immediate level of immunity. “Vaccines have timing issues in the sense that it does take a couple of weeks for the antibodies to build up,” Safdar explains.

I get it. A year into the COVID-19 pandemic, we’re all tired of it. We want our normal lives back. And now we’re being told that a vaccine is the only way to get back to some semblance of the way life used to be. But a new vaccine seems like scary stuff — until you look at the data behind the vaccines and understand how they’re developed, tested, and vetted. Then it becomes way less frightening.

With my compromised immune system, I can’t risk getting this virus. All I have to look forward to is a day, hopefully, when it’s a little safer to go out in public. No question — as soon as I can, I will get the vaccine. I’m just waiting for that notification…

But I have zero control over what everyone else will do. If you’re hesitant to get a vaccine when one is available, I plead for you to read the science and to remember this closing note from Dr. Safdar: “The vaccine serves a greater social good as well as an individual good.”

Jennifer Chesak is a Nashville-based freelance book editor and writing instructor. She earned her master of science in journalism from Northwestern’s Medill and is working on her first fiction novel, set in her native state of North Dakota.