My understanding of beautiful, ugly, attractive, and other aesthetic-related adjectives used to be extremely warped. Growing up, I begged to stop getting boxed braids because they were too “different,” compared to what the Nicoles and Ashleys of my class had.

I took family members’ advice of avoiding the sun — god forbid I get any darker. I routinely pinched my nose bridge and lips in a misguided attempt to shrink them. All of these actions were my ways of trying to assimilate into western beauty standards, what it looked like to be socially acceptable.

However, my idea of beauty changed in my early teens when I happened upon a Facebook comment from Hari Ziyad who said, “Black people do not have the ability to be ugly.”

I’d never heard of an idea like this before and did more meditating on the concept of beauty and how it relates to Black people. As I understood the idea more — that there is no such thing as an ugly Black person — I felt empowered enough to embrace my own personal style.

To seek out my own beauty routine, one that didn’t involve being obsessed with becoming “whiter.”

If you have one in mind, what you’re really revealing is a colonized version of what beauty means. In a world where beauty ideals adhere strictly to western standards of fair, thin, cis-het, and white people.

Black people, most of the time, will be thought of as “unattractive” because they are further from white ideals. This isn’t about personal physical, emotional, or sexual attraction, but the broader power structures that affect interpersonal relationships and social interactions.

Black people, particularly dark-skinned, Black women, are often relegated as unattractive without any interrogation of where that belief comes from. We are automatically assigned a place of physical inferiority without any hesitation. And the consequences of that are everywhere…

Serena Williams is continually masculinized because of her bulkier body type and is often compared as less svelte than her white counterparts, like Caroline Wozniacki. Leslie Jones, who suffered heinous harassment on social media, was called “ugly” and a “gorilla” by online trolls.

Even Black children are not shielded from this criticism — Blue Ivy, who has a more pronounced nose, has been taunted because of her looks.

Another reason society deems Black people “ugly”? Because our features are criminalized.

Media continually portrays Black people as the embodiment of ugly, dirty, and criminal. Even as crimes such as homicide are committed widely across all races, media continues to overrepresent crimes from Black and Brown people.

Even in fiction, representation of Black people has generally been depicted as criminals, affecting how we are seen from a young age. Black people always have to reactively challenge the narrative of being defined as unlawful.

Prescribing black people as “unattractive” has consequences beyond name-calling.

In non-European countries, the desire for fairer skin, a colonial import, is a health problem. In Nigeria, 77 percent of women use skin bleaching products to lighten their skin, and 59 percent of women in Togo use skin-lightening products.

These products are widely available despite attempts at government intervention. Even as these skin-lightening products make cancer more likely and having other health consequences, governments have issues keeping them from consumers.

Abroad, colorism is often targeted at African immigrants and Black tourists. In countries such as Italy and England, Black people routinely report being called “ugly” by strangers or being kept out of clubs and other establishments for being “too dark.”

In the United States, Black girls continuously struggle with their self-esteem as a product of being devalued in society.

In high school, I felt humiliated at my appearance, at my inability to conform. I used clothes as a way to hide my body and correct it. I wore large baggy shirts that enveloped my figure. I refused to take off my winter coat throughout the school day because I was embarrassed about how I looked and thought I was too ugly to have a style.

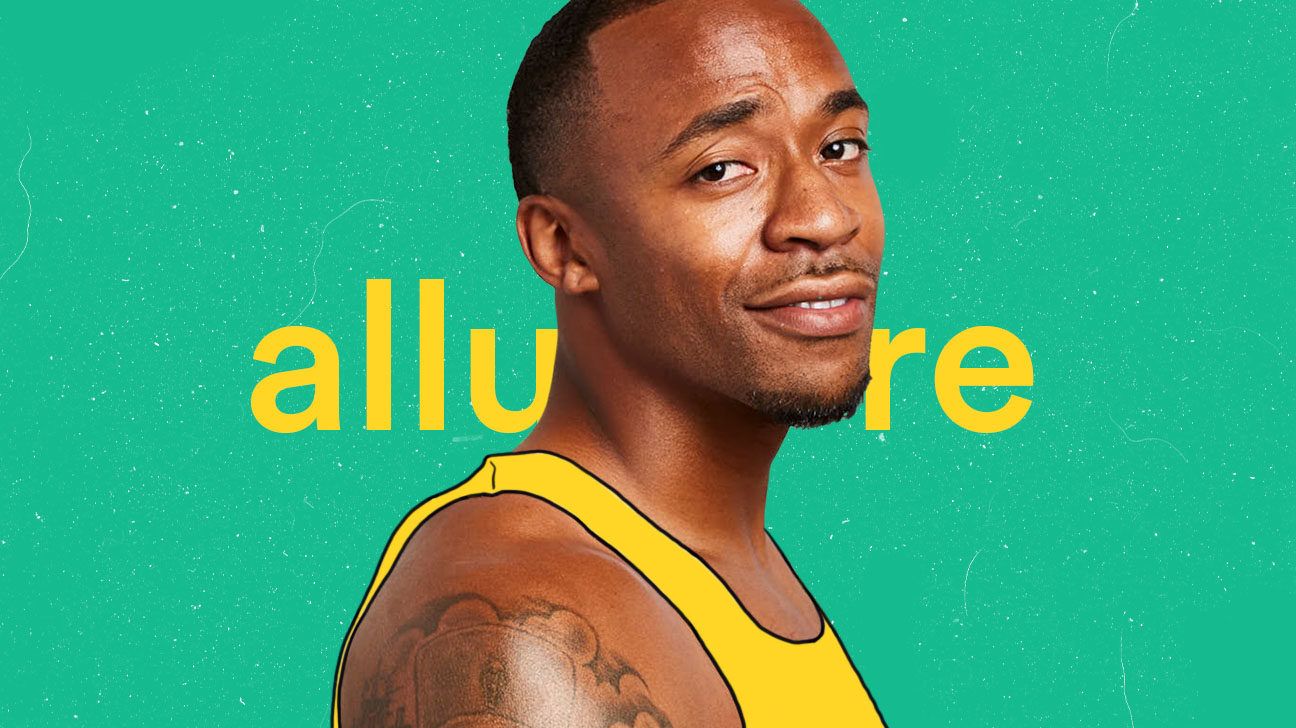

Now, in accordance with this new philosophy, I dress and present myself in line with how I want to express myself. I wear brighter colors — reds, yellows, whites, you name it — because I refuse to hide in demure shades if I am feeling bold.

I wear my hair the way I want to, whether that be nappy, in braids, in bantu knots, or straight; I refuse to let a fear of difference dictate how I style it.

I don’t use makeup as a tool to hide or shrink features like my nose, or body parts that I have been taught to hate. Instead, I embrace the lyricism of it, an opportunity to play with the gift that is my face.

I understand Black as beautiful. I fully embrace Black as alluring, even when other people, pop culture, and the world tell me otherwise.

Blackness isn’t beautiful in spite of whiteness. Blackness isn’t beautiful because white people find Blackness attractive (or fetishize it and pass that off as “attraction”). Blackness is beautiful without being compared to any standards, without the reassurance of corporations or anyone else, for that matter.

Black people can’t be ugly because whiteness shouldn’t get to define the metrics for what beauty means.

Whiteness has created and reinforced standards of beauty that only celebrate those with non-Black features; it has ruined the meaning of “beauty” and turned it into a racist term to shame difference.

The only way to have a developed understanding of “beautiful” and other terms of aesthetic is to broaden our understanding and disconnect “beauty” from white standards.

I refuse to hide. I choose to celebrate what I have been endowed with in the way that I choose. The world may hold on to their bias and define “attractiveness” and “beauty” as white, but as I reject these standards, I am refusing to participate and creating new rules.

Gloria Oladipo is a Black, woman, freelance writer who discusses all things race, mental health, gender, and more! Check out her thoughts on Twitter or Contently.