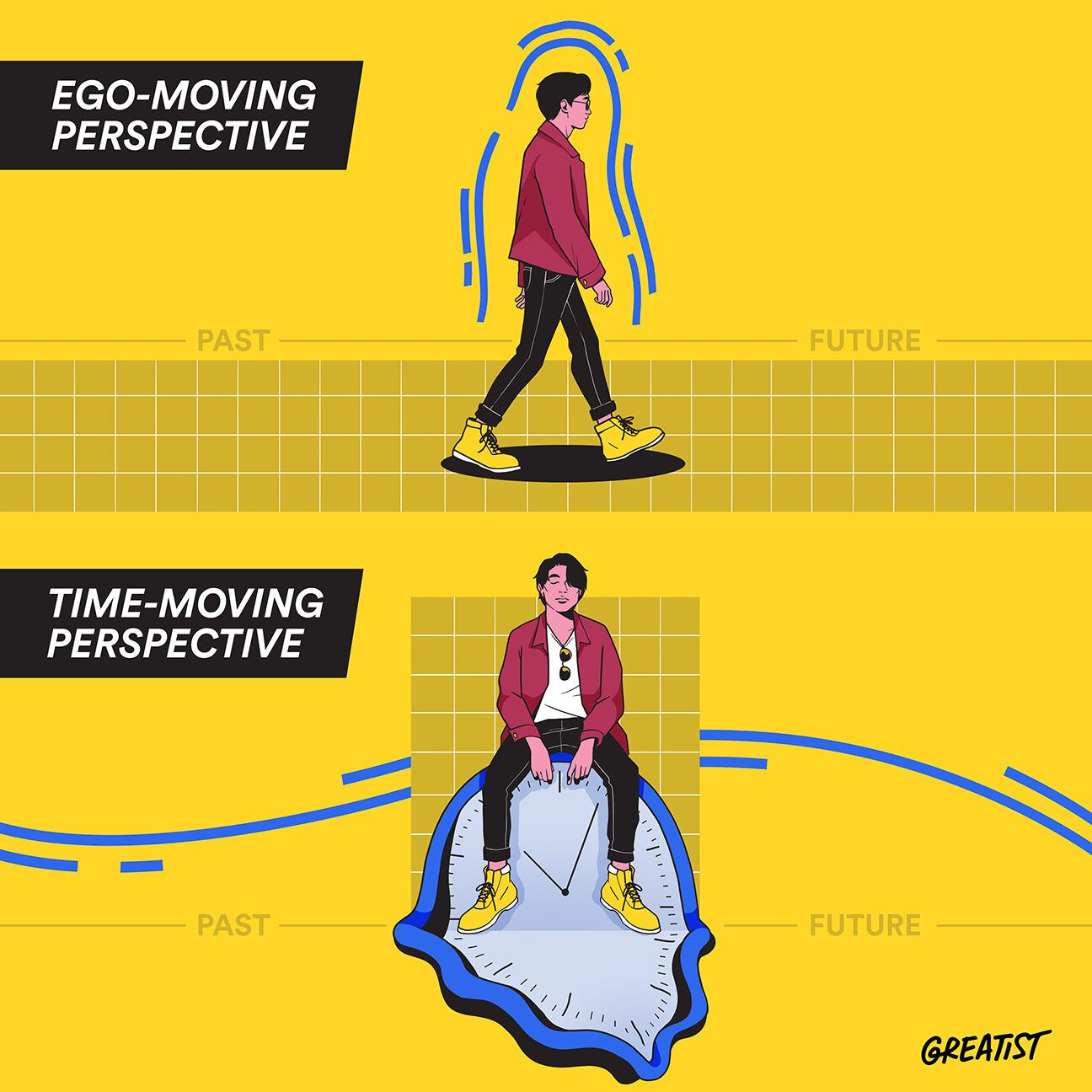

When a meeting on Wednesday has been moved forward by 2 days, when is it? The answer might seem obvious, but it’s not. Both “Monday” or “Friday” are the correct answer. This isn’t some kind of trick question, or even philosophical food for the thought. This simple query demonstrates the divide in the way humans look at time. These are the two main perspectives:

- If your answer was “Monday,” cognitive science and linguistics research suggests you have a time-moving perspective. This viewpoint conceptualizes you in the present moment as a stationary object, with time moving toward you as if it was a piece of chocolate on a conveyor belt.

- If “Friday” was your instinctual response, this suggests you have the ego-moving perspective. From this viewpoint, you (the responder) view yourself as moving toward events in future.

This “two types of people” grouping blew science TikTok’s mind in June, when Gregory Brown, via AsapSCIENCE, made a 48-second video on the phenomenon. Naturally, the discourse spilled over to Twitter, spiking interest in a cognitive science concept that’s floated around in psychology and linguistic circles for nearly 2 decades.

If you’re still confused, you’re not alone. Natalie Jeung, a licensed professional counselor at Chicago-based Skylight Counseling, made it easy for us: “When you’re talking about the ego-moving perspective, it feels like there’s more of a sense of control or agency in what you’re doing in your life,” Jeung says. “Ego in the psychology world means a sense of self. That’s what helps mediate between the judgmental thoughts that you have.”

In the context of the pandemic, for example, Jeung says that a person with an ego-moving viewpoint might channel coronavirus anxiety into something more productive. “There are tasks I can do and goals along the way to get to the end of the pandemic.” They would see looking at the time we’ve collectively spent affected by the virus as a physical tunnel to move through.

Someone with a time-moving perspective, in contrast, might try to gain a greater sense of acceptance. “I’m just going to adapt the things I can’t control.” They implicitly see this time as something mobile, like an approaching car, coming toward them, and might work on tolerating discomfort or practicing radical acceptance until it appears.

Though it’s been popularized before in 2017 (via The Cut), popular media coverage has largely relegated temporal perception to, “Look! This is a thing!” And for good reason: though many psychology and cognitive science researchers have studied the phenomenon further, little clinical research has been done on how this relates to larger mental health issues and personal coping skills.

There is some research, however. Experimental psychology researchers Albert Lee and Li-Jun Li established some ground on how temporal perception affects people’s perception of past events, relating their findings to potential clinical applications for mood disorders.

They believe it has the potential to help people manage psychological distance between themselves and unpleasant events. In 2014, they published their findings about memory recall and looking toward the future.

They noted that subjects recalling negative or unpleasant experiences were more likely to take an ego-moving perspective. Conversely, when primed to recall a pleasant event, they tended to take a time-moving perspective. When looking toward the future, however, Lee and Li found the exact opposite was the case.

Anticipating something pleasant in the future invoked the ego-moving perspective, whereas imagining something unpleasant triggered the time-moving perspective. This could mean that if you dread meetings, you might be more likely to respond with the time-moving perspective and believe that the Wednesday meeting has been moved “forward” to Monday.

It might help with rumination

Based on their findings, Lee and Li theorized that if people with depression could learn to adopt more of an ego-moving perspective, they might be able to alleviate rumination, a common symptom and thought pattern in depression.

“At the core, the finding suggests that the experience of time is flexible, and our minds are able to moderate the psychological distance between ourselves and temporal events (e.g., a haunting event in the past) as if they were objects in physical space (e.g., we “run” away from it or “leave it behind us”),” Lee tells Greatist via email.

For a clinical theory, Lee explains, taking an active, agency-filled ego-moving perspective could potentially make someone feel “comparatively better” than the “time is happening, and I’m just sitting through it” time-moving perspective.

But at the end of the day, however, their research couldn’t draw concrete conclusions. And 6 years later, not much else has been answered. No clinical research has been done on applying temporal perception in a clinical mental health setting, he says. And without empirical evidence, it’s premature to draw any conclusions on how to cope with stress or attenuate any mental illness symptoms.

Dr. Rachel A. Ross, M.D., Ph.D., psychiatrist at Montefiore Health System, specializing in anxiety and eating disorders, agrees with this limitation. “There is a correlate between how we see ourselves in the world and space. There’s not a correlate for how we see ourselves in time,” she says. “I think that’s really interesting, but I can’t think of how you would ask the question to be able to study it.”

Despite not being formally integrated as concepts for mental health management, Ross sees the ego-moving versus time-moving perspective fitting squarely into the wheelhouse of CBT, or cognitive behavioral therapy, albeit in an indirect way.

“To be able to use cognitive awareness of your perspective, to be able to be flexible within it, is totally possible but it’s not easy,” she says. The more you practice a given way of thinking, the easier it gets, and therapy can help. “CBT is exactly that. If you’re motivated to start with awareness of a particular habitual way of responding, behaviorally or cognitively, you can with practice changing that response.”

Understanding the relationships between behaviors, thoughts, and situations, people engaged in CBT can increase their awareness of a habitual response, whether that’s in how they feel or how they act in a particular stressful situation. If they want to change that, CBT can help them think through why they behave that way and brainstorm more effective ways of reacting.

For example, if the thought “I never get anything done in time” comes up often, an alternative explanation including one’s predisposition to ego-moving or time-moving perspective might help. “It gives you the opportunity to beat yourself up a little less,” Ross says.

To therapist Natalie Jeung, fitting the distinction between ego-moving and time-moving perspectives into a practical approach to coping makes perfect sense.

In extreme cases, an ego-moving mindset could cause people to try and gain unrealistic control over everything in life; whereas an extremely time-moving mindset might result in a sense of complete helplessness — “like you’re just a bystander in life.”

That’s why, no matter what mindset a person is predisposed to, practicing flexibility is above all an important skill.

“We’re looking for this spectrum where you can move fluidly between the two perspectives where you can accept things out of your control, but you’ll be able to feel like you can control other things,” Jeung says.

But having any internal sense of control or agency over one’s life doesn’t have to be an all-or-nothing proposition. People aren’t permanently stuck in either perception of time, though they might be predisposed to looking at the world one way or the other.

According to Jeung, that’s where framing comes in during therapy. Through framing or reframing long-standing thoughts and beliefs, clients are able to contemplate and internalize different perspectives. “Moving from a more negative tone to a more positive tone can be helpful, even if the overall message is exactly the same,” she says.

She gives the reframe example of a common sentiment: “I make a mistake, which people will see, meaning I’m bad at my job.” In a positive reframe, a client might instead be able to think: “I made a mistake and people might have seen, but I learned from it.” In either case, the information is the same — I made a mistake and other people know — but there’s a beneficial shift in perspective.

Although there’s still more research to be done on just exactly how much temporal perception might influence our ability to cope with stress and life’s uncertainties, both Ross and Jeung have made clear that the already evidence-proven benefits of CBT are available. “The reality is that we do have some agency about what we can do to feel better in our lives,” Jeung says. No matter your initial mindset toward the future, there’s still room for growth and change.

Patricia Kelly Yeo is a freelance writer and journalist covering health, food, and culture. She is based in Los Angeles. Find her being mostly professional on Twitter.